I’m not a car enthusiast (or a ‘petrol head’ as they are known locally) — far from it. I learned to drive late in life, already in my 30s when I started driving in Adelaide. By then, I had a very clear idea of the kinds of cars I wanted. I’ve always loved distinctive, retro-looking cars but also something that felt like me.

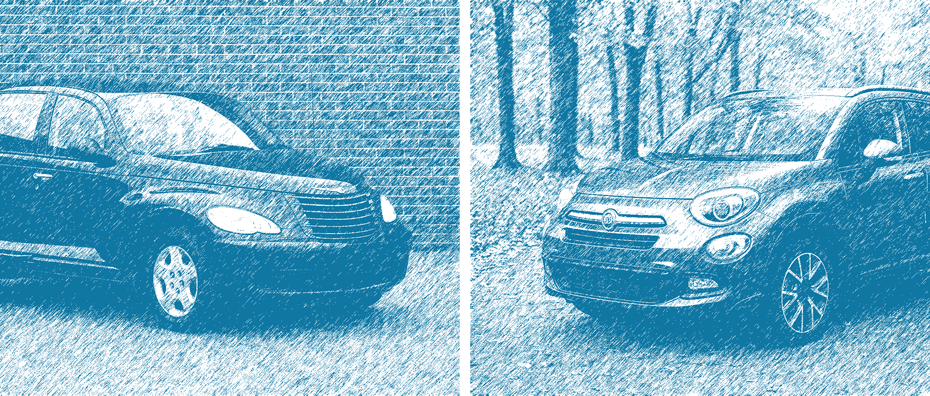

Ignoring the well-meaning advice to choose a sensible first car like a Toyota or Mazda, I bought a second-hand Chrysler PT Cruiser. Some friends joked that my car looked like a hearse; others said it resembled a gangster mobile. I called the car Burt because ‘he’ looked stocky and American, and the name just fit. After seven years, however, Burt began to cause trouble. With Chrysler abandoning the model and parts becoming rare, each service visit grew more complicated and expensive. Eventually, I sold Burt – to a buyer also named Burt, who bought the car for his wife!

My second car is a second-hand 2015 Fiat 500X. It carries the retro charm of the Fiat 500, but with the practicality of a mini-SUV that lets rear passengers enter without acrobatics. I call the car Totò, in honour of the character in ‘Cinema Paradiso’, the movie. But last month, I learned that the authorised service centre I’d relied on for eight years no longer accepts Fiats.

Fiat is now part of Stellantis, formed from the merger of the French PSA Group and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA). For reasons only they truly know, Stellantis has been steadily reducing its physical availability in Australia. Citroën was pulled out in 2024; Fiat’s model line-up has been trimmed; and the 500x has quietly yanked off the market. The service centre suggested me to call Stellantis, with the person at the end of the line informing me that there are no authorised Fiat service centres in Adelaide. The nearest service centre is in Melbourne, Victoria. An eight-hour drive away.

With the local service ecosystem disappearing, I’m forced to consider selling Totò and finding my next car. The trouble is: so many modern cars look the same. Sleek, futuristic even – but uninspiring to me. Among the distinctive ones that remain, most are outside of my budget or my preference. I generally drive simply to get from A to B, but I still want to enjoy the experience.

At the moment, I’m leaning towards a Škoda mini-SUV – keeping with the European theme and choosing something slightly left-field. While Škoda doesn’t have the quirky charm of the PT Cruiser or the 500X, it feels like something I could be content with. And being part of the Volkswagen group gives me confidence that support will continue.

What does any of this have anything to do with Marketing?

Quite a lot, actually.

My experience is a small but tangible example of how the principles of Marketing Science – especially the Laws of Growth as promoted by the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute – apply far beyond consumer-packaged goods. These laws hold across categories as varied as shampoo, financial services, home appliances … and cars.

- Consumers can become category buyers at any time. Planned or unplanned: a breakdown, an accident, a model being discontinued, a shift in household needs — all can instantly turn a non-buyer into a category buyer. This happens all year round. When it does, consumers tend to gravitate towards big brands with established mental availability. However, this is not guaranteed. Brands that advertise only seasonally or narrowly to selected segments risk missing the millions of potential buyers outside that window or target. If a brand is not known, it is less likely to be considered – even if it is objectively good.

- Distinctiveness matters – even for cars. Many iconic designs are disappearing: the PT Cruiser, the Volkswagen Beetle, and the Fiat 500X. Sometimes this is due to cost pressures, sometimes shifting tastes. However, as distinctiveness fades, models begin to look increasingly similar. Contrast this with MINI – instantly recognisable, even as it expands into SUVs. There’s something unmistakably on-brand with every model iteration.

- Distinctive Assets go beyond logos. Just as Toblerone is recognised by its triangular packaging and Coca-Cola by its bottle silhouette, car brands are remembered through their shapes and designs. Consumers may recognise Toyota, Mazda, KIA, or Rolls Royce logos – but can they recognise a brand from a two-second glimpse of a car driving past? Distinctive forms on the road become mental availability cues for other drivers and pedestrians. When these designs disappear, those links weaken over time.

- Physical availability goes beyond the point of purchase. I would argue that the importance of physical availability for durables and cars isn’t just at the point of purchase. It is also about continued usability. Fiat can still be ordered online in Australia, but the lack of after-sale service in many places provides major physical availability challenges. When manufacturers discontinue their after-sales service, it also affects the probability of buyers keeping the car, and considering the same car brand for their next purchases. Why would somebody stay with a brand for their subsequent purchase, if there is no after-sale service?

The Final Words

It’s a mistake to assume that the Laws of Growth apply only to fast-moving consumer goods. Mental availability and physical availability are critical for any brand that wants to get bigger – or stay big – regardless of the category. Cars, chocolates, loans, fragrances, insurance, airlines, coffee machines – the patterns are consistent. Brands grow by being easy to mind and easy to find!

PS: If I do get a Škoda, any suggestion for a Czech name for the car would be appreciated as well!